Why the novel Steppenwolf feels so personally reflective

A time of stepping inside myself … to enter the Magic Theatre of self-examination …

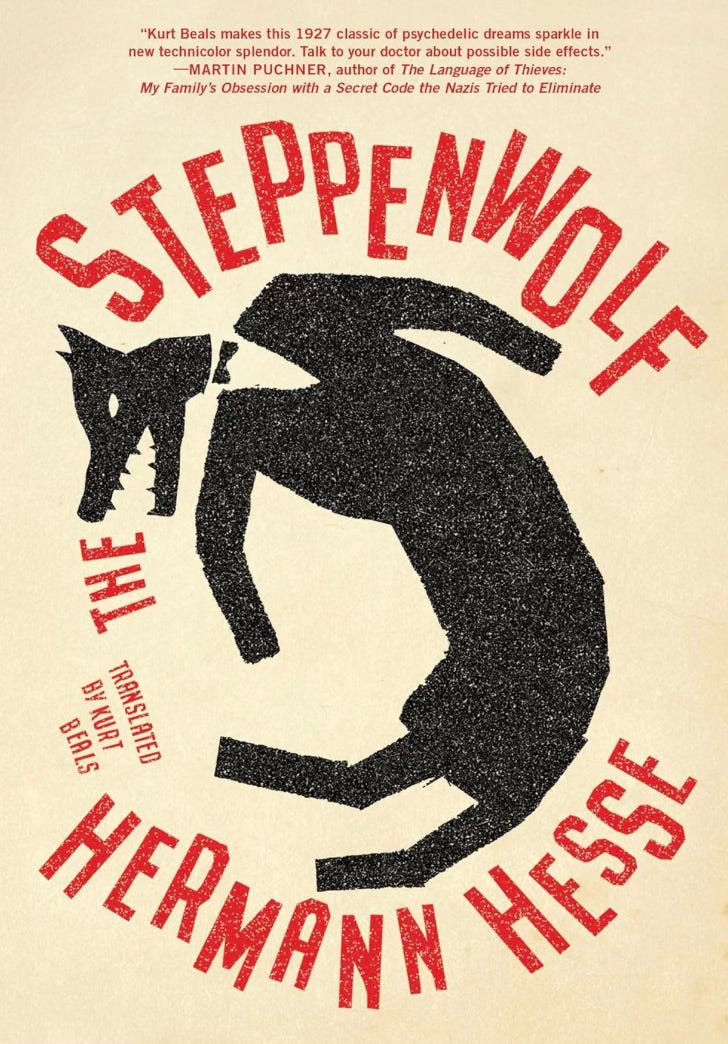

My digital edition of Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse (1927) contains an author’s note, written in 1961. Nobel Prize recipient Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) wrote that it was his most often misunderstood novel, and that some people reacted to it “oddly” – not only due to its poetic writing but, he thinks, due to generational or self-identification reasons. He wrote the “self-portrait” novel as a 50-year-old German-Swiss man whose character Harry Haller feels himself to be half-human and half-wolf – i.e., half-civilized and half-instinctual – which is also interpreted as an ode to self-examination. American author Kurt Vonnegut said Steppenwolf was “the most profound book about homesickness ever written.” It feels personally reflective for me.

Steppenwolf is a not only about the dual nature of humans, but about the many selves that live within Harry Haller – and within us. For many readers, the novel becomes a mirror, and is particularly poignant in midlife or later, when asking ourselves, not “What should I do?” but “Who am I really?”

Putting the novel in its historical context adds another dimension. Hesse was writing between two world wars, at a time when Germany was grappling with its identity. His themes include alienation and the lure of Eastern philosophy.

As a female reader post-midlife adds two additional dimensions that I did not notice in the blush of idealistic youth when I first read the novel. I now find new meaning in the novel’s longing for reintegration, not as the angst of youth but as a mellowed desire for wholeness. Harry Haller has deeply masculine (and often misogynistic or idealized) perceptions of women yet figures like Hermine and Maria act as guides leading Haller to transformation.

I reflect on Harry Haller again, and how much of his character I am now accepting, rejecting, or making peace with.

Hesse’s style in Steppenwolf is intentionally disorienting, with both realistic narrative and psychedelic episodes (especially in the Magic Theatre section). His tone is existential and mournful but compassionate and redemptive. Hesse wants readers to experience Harry Haller’s psychic unraveling and resurrection.

Is Steppenwolf relevant today, 98 years after its publication?

Profoundly so. Today’s world is full of people feeling fractured by competing identities, anxieties, and social pressures. Steppenwolf speaks to the digital-age reader who juggles curated personas on social media, hidden longings, and internal contradictions. The novel asks us to stop numbing ourselves and to step into the Magic Theatre of our own soul, however bizarre or painful it might be to do so.

The novel reminds readers that transformation and change often come through “internal surrender to the unknown” not through external success — a message needed now as it was in 1927.

Steppenwolf can feel dated in some gender roles, and at times indulgent in its philosophising, but, like Haller, it’s not trying to be “perfect.” Instead, it’s trying to be authentic. And that’s why I like this novel and will read it again before I too end my century.

*****

Additional article in Rainy Day Healing about Steppenwolf: Making my peace … with stepping inside myself “This kind of quiet, honest reflection is exactly what makes Rainy Day Healing such a special space.” Chaz T., USA

Can’t see the whole article? Want to view the original article? Want to view more articles? Go to Martina’s Substack: The Stories in You and Me